When the world leaders gathered in New York for the 80th session of the U.N. General Assembly, Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa’s address was among the standout moments. It was the first time in nearly 60 years that a Syrian leader was addressing the U.N.

Mr. al-Sharaa’s speech came weeks ahead of elections in Syria. Mr. al-Sharaa, a former al-Qaeda jihadist, has claimed that this election will facilitate bringing together a transitional government in place. Citing the absence of the required infrastructure for a popular poll, the elections are being conducted using a tightly-defined electoral college system with several pre-conditions. The elections, though not representative, will usher Syria into a new political scenario after decades of the Ba’ath party rule.

One of the oldest-inhabited regions in the world, Syria has had a fraught relationship with democracy. Over the years, as power has changed hands, the country’s political future seems to have slipped further away from the hands of Syrians.

The modern Syrian state and establishment of Ba’ath rule

The grounds for the existence of the modern Syrian state can be traced back to the early 20th century. Just as the First World War wound down, the Great Arab Revolt of 1918 shook the region, bringing an end to centuries of Ottoman rule. What followed was the division of territories among the French and the British authorities, and subsequently, the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 was implemented to enable France to secure control over the Greater Syria region.

By 1946, however, Syria declared independence from French control and Sunni leader Shukri al-Quwatli took over the reigns as the first President of independent Syria.

What followed was decades of military coups and counter-coups, as regional and military discontent forced the change of power. In the meantime, Arab nationalism continued to gain popularity in the region, as the Ba’ath party (founded by Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar) amassed followers. On March 8, 1963, the party’s emboldened military wing led a successful coup to grab power. They established the National Council of Revolutionary Command and implemented a state of Emergency across the nation of Syria, that lasted until 2011.

Hafez Al-Assad, the then President of Syria

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

An intra-party coup, three years later, established General Salah Jadid as the ruler of Syria, and gave his right-hand man Hafez al-Assad a more prominent role in Syrian politics. As internal strife played out, the country faced external threats. Syria was pulled into the Six-Day war in 1967, and came out of it losing the Golan Heights to Israel. Back home, al-Assad lost faith in Jadid’s leadership and in 1970 imprisoned him and his supporters in a bloodless coup. A year later, he formally took charge as President and commenced the 53-year long rule of the Assad family.

The family rule and Ba’ath party’s place in Syrian politics was formalised with the 1973 Constitution. The most significant clause in the Constitution was Article 8, which indirectly put in place a one-party system. Hafez al-Assad’s rule was marked by an increasing consolidation of power into the hands of the minority Alawite population, which al-Assad himself belonged to. After his father’s demise in 2000, Bashar al-Assad formally took over the reigns of the Ba’ath Party and Syria.

Continuing the Ba’ath legacy

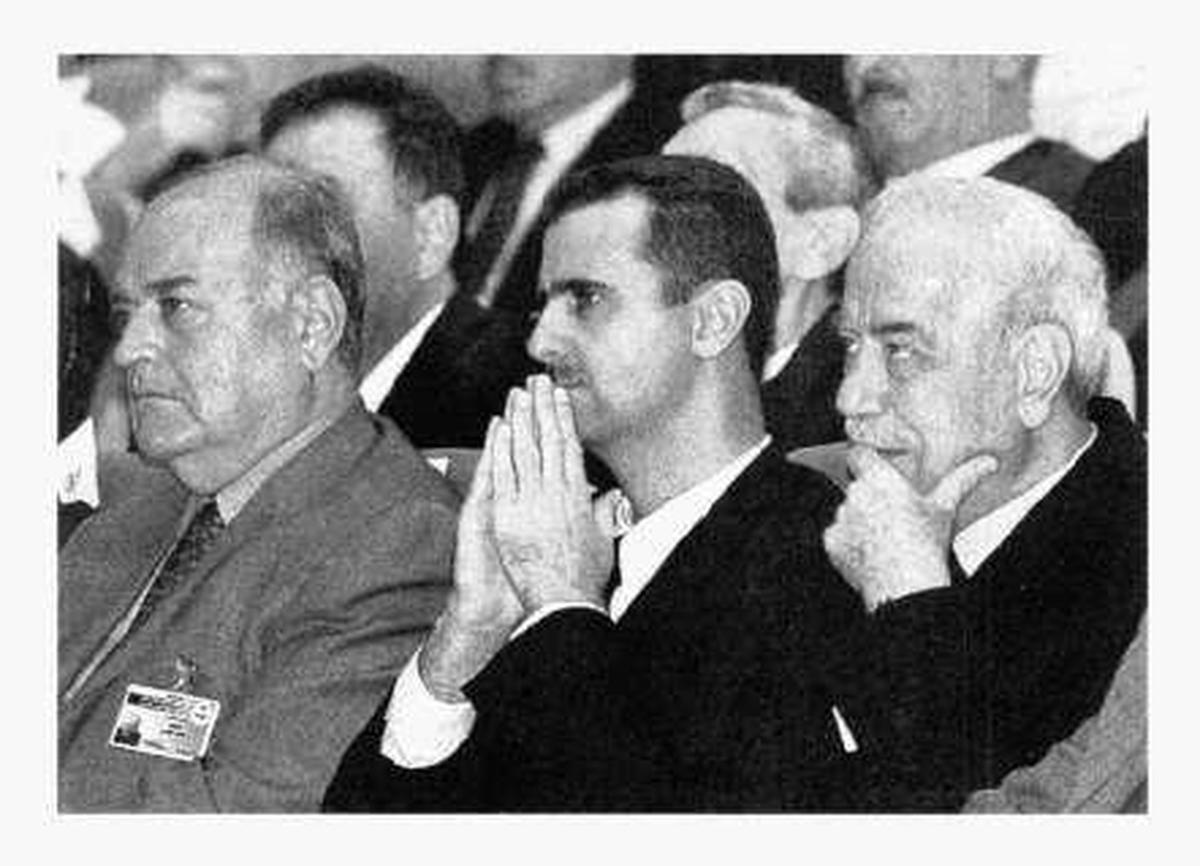

Mr. Bashar al-Assad (centre), son of Syria’s late President, Hafez al-Assad, attends a conference of the ruling Ba’ath Party in Damascus in June 2000

| Photo Credit:

AP

An ophthalmologist from London who was called back to learn the political ropes following the death of his elder brother, Bashar al-Assad sought to project a cosmopolitan image. His rule started with the release of 600 political prisoners. Over the years, select private media organisations were allowed to operate, and Damascus Securities Exchange began its operations in 2009.

The consequence of attempting to set himself apart from his father’s iron-fisted control of Syria meant that previous dissenters found Damascus safe to return to. The Muslim Brotherhood, which had been outlawed by Hafez al-Assad, announced the resumption of its operations less than year after the son took over. As President then, Bashar al-Assad found himself returning to his father’s playbook, and soon began the detention of Parliamentary members and pro-reform activists.

The U.S. was quick to register its displeasure with Mr. al-Assad’s regime. Meanwhile, Mr. al-Assad got the diplomatic wheels moving and between 2006 and 2010, and held dialogues with the European Union, the U.S. and France. He also established diplomatic relations with Iraq and Lebanon. During this time, Syria held elections in 2003 and 2006 in which the Ba’ath Party retained power.

2011- Syrian spring of resistance

In Syria’s Daraa, months after Zanul Abideen Ben Ali’s government was overthrown in Tunisia, protests erupted against the al-Assad government in March 2011, after military police arrested school students for anti-government graffiti. Anti-government protests, which had been trickling in from different parts of Syria since January swept across cities. The common demands included repeal of the Emergency law, removal of Article 8, and the departure of President al-Assad.

Despite the government using lethal force against protestors, the uprising continued. Syria, a highly diverse country, became fertile ground for sectarian politics to find its feet.

Mr. al-Assad was forced to concede to some of the demands. Emergency law was lifted in April 2011, and some political prisoners were released. The following year, a new Syrian Constitution came into effect, introducing a multi-party system. It also, on paper, expanded political rights and the freedoms allowed to Syrians. The President’s term was also limited to seven years, but not retroactively. These steps couldn’t stop the country from plunging deeper into a full-blown civil war.

Allegations of chemical weapons attack by the regime attracted severe condemnation worldwide and Syria found itself increasingly isolated on the world stage. By 2013, the U.S. actively entered the frothy war by promising non-lethal support to rebels in northern Syria. In 2014, a growing problem under Mr. al-Assad’s nose bloomed into the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Its militants declared a caliphate comprising several parts of Syria, including parts of Aleppo, and within a year established their presence in the ancient city of Palmyra.

Also read | Twelve days that shook Syria

Foreign intervention

The fact that Syria’s war was playing out against the backdrop of regime change in Libya meant that Syria became a live experiment for Western nations on how to influence internal politics. The U.S. was not happy with Libyan results, and the Baa’th regime being a powerful ally to Iran meant that Western nations were not going to settle for anything less than complete surrender. Western nations, along with Gulf Arab countries and Turkiye seeking the removal of Mr. al-Assad formed one bloc. Meanwhile, Mr. al-Assad had Russia, Iran and Iraq on his side.

Four years on, the West now eager to find a solution to the Syria question, adopted Resolution 2254 in the U.N. in 2015. It called for peaceful negotiations between the regime and the rebels, a transitional government in Syria, and eventually free and fair elections.

However, for Mr. al-Assad, the reprieve came from closer geographical quarters. Russia’s eagerness to become an influential player in West Asia by countering U.S. influence, and protecting its defence interests, including the Tartus naval base, introduced a new dimension in the war. The results were swift and by December, Homs was back under the regime’s control. By March 2016, Palmyra was freed from ISIS control, and Aleppo followed soon after. Iran had also mobilised Shia militias, including Hezbollah, to assist Mr. al-Assad.

In November 2016, Mr. al-Assad gathered together a couple of Western journalists and relayed the comfortable position his regime had now achieved. He ended up crediting his longevity in Damascus to the war itself. According to Mr. al-Assad, the war made Syrians realise the “value of the State”.

What finally put a pause on the now seven-year old civil war was the September 2018 agreement between Russia and Turkiye. The positive momentum in their diplomacy led to the establishment of a demilitarised zone in Idlib region – the last major stronghold of anti-regime forces.

Assad chapter comes to a close

By 2020, Mr. al-Assad with help from Russia and Iran had gained back control of 70% of the country. Over the next few years, Syria began to return to the Arab fold, and the President held dialogues with the UAE, Turkiye, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia. On the homefront, he directed the rebuilding of war-torn cities.

However, the al-Qaeda-linked Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) was continuing to operate its own government in Idlib. Headed by Abu Mohammad al-Jolani (now Ahmed al Shara), the HTS had emerged as the strongest anti-regime militia, and in Idlib was running its own bureaucracy and judicial system. Taking back Idlib after eradicating HTS became one of the goals for Mr. al-Assad, along with absorption of Kurds under the Syrian state, and the controlled exit of U.S. military presence.

By the time 2024 came around, the toll of pandemic years, devastation caused by a deadly earthquake, and a plummeting economy meant that there was a burgeoning dissatisfaction among the population. Add to this Russia’s war in Ukraine and Hezbollah’s skirmishes against Israel, and the al-Assad regime found itself vulnerable. The HTS also recognised this and decided to move forward. With Turkiye’s blessings, the HTS launched an offensive on November 27 from Idlib, moving forward swiftly across major cities without any resistance from the Army. Within 12 days, the al-Assad rule that had survived wars across and within its borders came to a close.

The then Syrian Prime Minister Mohammad Ghazi al-Jalali supported a peaceful transition of power, while the Syrian Army declared Mr. al-Assad’s defeat. Mr. Jolani of the HTS (Ahmad al-Sharaa) was installed as Syria’s new leader.

Syria’s political future

Now, the HTS and the Syrian National Army (a proxy of Turkiye) form one front on the Syrian political stage, while the Kurdish groups continue to assert autonomy in other regions. Towards the south, local militias have taken control over some territories, and the Alawite population in the coastal regions remain loyal to the Assads. Mr. Sharaa has given unto himself a fractured Syria.

With the Ba’ath Party freezing its operations, there appears to be no organised political opposition to Mr. Sharaa. Salih Muslim Muhammad, leader of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the main party of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, in an interview to The Hindu had stated how the Syrian population does not wish to revert to a centralised regime. “Those who are controlling Damascus insist on forming a very strict, centralised regime as it was before, but with a different ideology — before there was a Baathist regime, and now they are trying to make it a Salafi regime,” he had said.

The months following Mr. Sharaa’s takeover reflects this statement. Several reports of attacks on minorities, including a massacre against the Druze community in April this year have raised alarm bells.

Mr. Sharaa’s plans for the election also don’t inspire hope for an inclusive political future for Syria. While one-third of the Assembly’s 210 seats will be appointed directly by the President, the rest will be voted on by electoral colleges in each district. A lack of transparency in how the subcommittees and electoral colleges will be chosen, along with the exclusion of Druze-majority Sweida province and Kurdish-controlled areas in the northeast from the process, has given some glimpse into Mr. Sharaa’s intentions.

As Mr. Sharaa moves in New York circles asking for sanctions on Syria to be waived, back home the HTS lacks administrative control over the complete Syrian territory. How and in what measure he navigates the complex ethno-political equations will determine whether Syria gets on the road to true democracy.